In contrast to the simple mouldings covered in previous posts, in which each moulding consists of a single curve, the cyma recta and cyma reversa are examples of compound mouldings: mouldings that consist of two or more curves. In the case of the cyma (from the Greek for ‘wave’) mouldings, there are two curves in each, an ovolo and a cavetto, arranged in series.

The cyma recta consists of an ovolo at the bottom and a cavetto at the top:

In the cyma reversa, the order is reversed, with the cavetto at the bottom and the ovolo at the top:

The cyma recta and cyma reversa are examples of the general group of compound curves known as ogees (pronounced with a soft g), defined as double curves or arcs, one concave and the other convex, joined at a point of inflection, and where the unjoined ends of the curves or arcs point in opposite directions and have parallel tangents; that is, if the ogee curve were in a road you were travelling on, you would be travelling in the same direction upon exiting the curve as you were when entering it. In the recta, the ends extend horizontally; in the reversa, they extend vertically.

In terms of their structural and psychological functions, the recta is a supporting moulding with an ‘upwards’ emphasis, and the reversa is a terminating moulding with an ‘outwards’ emphasis.

The cyma mouldings come in infinite varieties and expressions, depending on whether the curves used are arcs, ellipses, parabolas, or hyperbolas, and on the flatness or depth of the profile. The relative size of each curve in the profile can also be varied; a cyma reversa with a small cavetto topped by a large ovolo, for example, has a much more robust appearance than one with a large cavetto under a small ovolo.

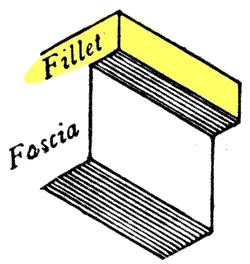

Cymas are typically better employed as the uppermost or lowermost mouldings in a group than they are in an intermediate position. They are almost always combined with small fillets above and below, to isolate and define them against the background planes of the wall or soffit, or against other moulding profiles in the group.

As for remembering the difference between the two, all I could come up with is that the recta resembles a breaking wave, which, if you were surfing it, might mean you were about to get ‘rect’. Not great, but if you have a better mnemonic please let me know!