As covered in the previous series on minka structure, the structural logic of Japanese buildings results in two spatial zones: an inner jо̄ya (上屋, lit. ‘upper building/roof’) part, which is the area bounded within the ring of taller, inner posts (hashira 柱) called jо̄ya-bashira (上屋柱); and the geya (下屋, lit. ‘lower building/roof’), the outer, perimeter space between the jо̄ya-bashira and the ring of lower, outer posts (geya-bashira 下屋柱) that constitute the external perimeter of the building, whether in the plane of the external walls or as freestanding ‘verandah’ posts. The geya might be thought of as an infilled under-eave area, floored and walled to bring the space within the interior. The jо̄ya - geya spatial organisation is the result of the structural organisation of the building; in terms of residential architecture, it originated with the shinden (寝殿), the residential architecture of Heian period (Heian jidai 平安時代 794 - 1185) nobility.

Diagrammatic section and plan of a shinden, showing the two rings of posts that delineate the inner moya (母屋, lit. ‘mother building/roof’) space, corresponding to the jо̄ya of the minka, and the outer hisashi (庇, ‘eave’) space, corresponding to the geya.

Like the shinden, old minka often had geya on all four sides, with rows of jо̄ya posts at the boundary between the jо̄ya and the geya, as seen in the famous Furui house below.

Plan of the former Furui family (Furui-ke 古井家) residence, Hyо̄go Prefecture, a three-room layout minka, showing the jо̄ya (上屋) space (white), and the geya (下屋) space (the blue perimeter band). In this relatively primitive minka, the geya space has largely not been rationally incorporated into the plan to form closets, etc.; rather, the jо̄ya posts are for the most part freestanding in the interior spaces.

Transverse section of the Furui house, with geya shown in blue.

Longitudinal section of the Furui house, with the geya shown in blue.

In the spacious shinden, the wide geya formed a natural circulatory passageway around the inner moya; utilitarian functions like storage were taken up by other buildings in the shinden complex, so the shinden plan itself could remain architecturally ‘pure’. The narrower geya of the minka might also partially function as a circulation space, i.e. as the ‘verandah’ (engawa 縁側), but it was often used to house utilitarian elements that could practically fit within its depth; or perhaps it was rather the case that these elements evolved to fit within the geya. They included shelved cupboards (todana 戸棚), closets (oshi-ire 押入), the Buddhist alcove (butsuma 仏間), and the ornamental alcove (tokonoma 床の間 or toko 床) that is the subject of this post.

In this Muromachi period minka, the development of a tokonoma is hinted at in the utilisation of the geya space in the omote to house the Buddhist altar (butsudan), Shintо̄ shrine, and other ornamental items. Furui family (Furui-ke 古井家) house, Hyо̄go Prefecture, designated an Important Cultural Property.

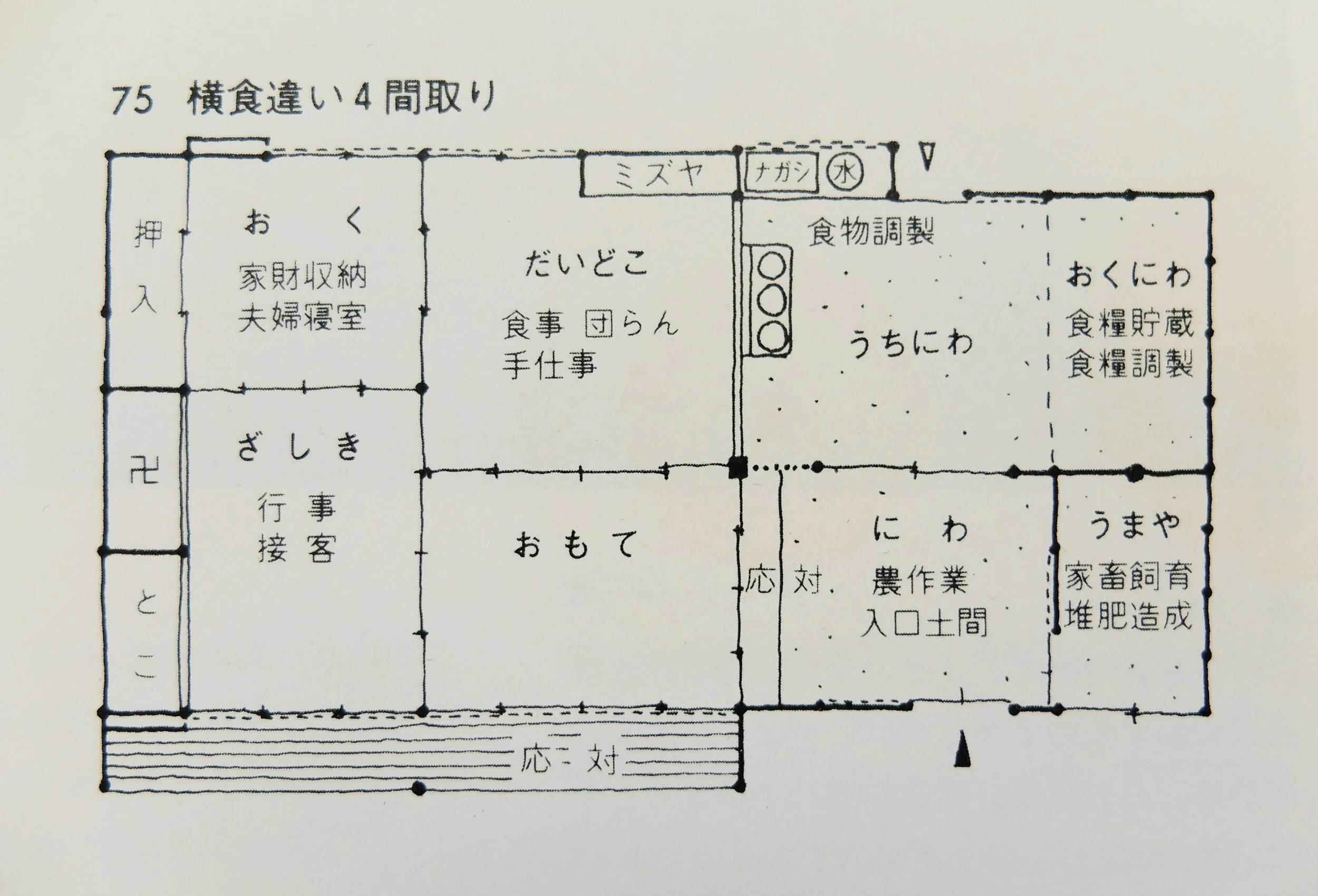

The plan below is a good example of how the geya space was utilised in minka. The toko (とこ) is placed in the gable-end (tsuma 妻) geya, along with a Buddhist altar (butsudan 仏壇) and other objects related to worship and ceremony.

The geya space in this minka is more typical than that of in the Furui house in that here, as in most minka, it is partial or ‘broken’, not running the full circumference of the building. It contains ornamental alcove (toko とこ), Buddhist alcove (butsuma 卍), bath (nyūyoku 入浴), storage (shūnо̄ 収納), urinal (shо̄ben 小便), and verandah (engawa, unlabelled).

Examples like the minka above are used to argue in favour of the theory that the tokonoma has religious origins. This theory, which has become a commonly believed ‘myth’ through its presentation in works such as the Edo period Ka-oku Zakkou (家屋雑考 ‘Miscellaneous Thoughts on Houses’, 1845) by Sawada Natari (沢田 名垂, 1775 - 1845), is that the tokonoma began in the Kamakura period (Kamakura jidai 鎌倉時代, 1185 - 1333) in the shaku-ke or shakke (釈家), the residences of Buddhist priests or monks (sо̄ 僧), who would hang Buddhist art on the wall, place a thick board called an oshi-ita (押板) on the floor before it, and on the oshi-ita place the ‘three-piece set’ (mitsugusoku 三具足) of candlestick (shokudai 燭台), incense burner (kо̄ro 香炉), and vase (kabin 花瓶); this arrangement was later adopted into samurai residences (buke jūtaku 武家住宅).

Another account of the origins of the tokonoma holds that it developed as a place to appreciate the scroll art (jiku-sо̄ga 軸装画) imported from China in large volumes from the Kamakura Period onward.

A third theory is that the jо̄dan-koma (上段小間), the small raised rooms ‘within’ the zashiki, gradually simplified and shrank over time to become tokonoma, called among other names the jо̄dan-doko (上段床), that retained both the tatami-laid floor elevated a step above the zashiki and the black lacquered (kuro urushi-nuri 黒漆塗り) floor sill (kamachi 框) of its progenitor and namesake.

This third account is thought by Kawashima Chūji to be the most rational and persuasive; even today, the floor of a ‘standard’ toko is typically tatami-laid, and Kawashima writes of hearing that on certain occasions, such as tea ceremony, a distinguished guest might sit in the toko without this being considered a breach of etiquette. It is thought that later, with the development of the arts and crafts (bijutsu kо̄gei 美術工芸) in general, and the ‘ways’ (dо̄ 道) and schools (ryū 流) of tea ceremony (sadо̄ 茶道), flower arrangement (kadо̄ 華道), and incense appreciation (kо̄dо̄ 香道) in particular, that the tokonoma transformed into a place exclusively for the appreciation of interior decorative objects (shitsunai sо̄shihin 室内装飾品). Then, over the course of time and with the addition of increasingly sophisticated woodworking techniques and proportion in design, the tokonoma spread almost universally to the common minka, in the process becoming an indispensable element of the zashiki, and the one most closely associated with it.