In the foothills of Mount Matsukura (Matsukura-yama 松倉山麓) on the western outskirts of Takayama City (Takayama-shi 高山市) in Gifu Prefecture, there is a preserved gable-roofed gasshо̄-zukuri (合掌造り, ‘praying hands style’) minka called the Wakayama house (Wakayama-ke 若山家). This house originally stood in Shо̄kawa-mura Shimotaki (荘川村下滝), and is said to have been built in the early years of the Hо̄reki (宝暦) era (1751 - 1764). The majority of the gasshо̄-zukuri minka in Shо̄kawa village (Shо̄kawa-mura 荘川村) are either hipped (yose-mune-zukuri 寄棟造り) or what in English is variously called hipped-and-gabled, gable-over-hip, or Dutch gabled (iri-moya-zukuri 入母屋造り), and it should be emphasised that gasshо̄-zukuri like the Wakayama house, while gable-roofed in appearance or ‘style’, retain a hipped structure beneath, with hip rafters (sumi-sasu 隅叉首 or sumi-gasshо̄ 隅合掌) and gable-end rafters (mukо̄-sasu 向う叉首 or mukai-sasu 向い叉首). The village of Shо̄kawa lies on the upper reaches of the Shо̄ River (Shо̄kawa 荘川), which drains into the Sea of Japan; in the mountain villages of the Tonami district (Tonami chihо̄ 砺波地方) downriver, the transformation of the hipped roofs of the minka into clipped-gable roofs (kabuto-yane 甲屋根) can be seen, with the gable gradually expanding until the form is close to a pure gabled style.

These facts seem to clearly indicate that the gable-roofed style of gasshо̄-zukuri of Shirakawa-mura and the Gokayama district (Gokayama-chihо̄ 五箇山地方) has not remained unchanged from long ago, but rather that the gabled roof has evolved from the hipped roof, in response to the functional demands of sericulture.

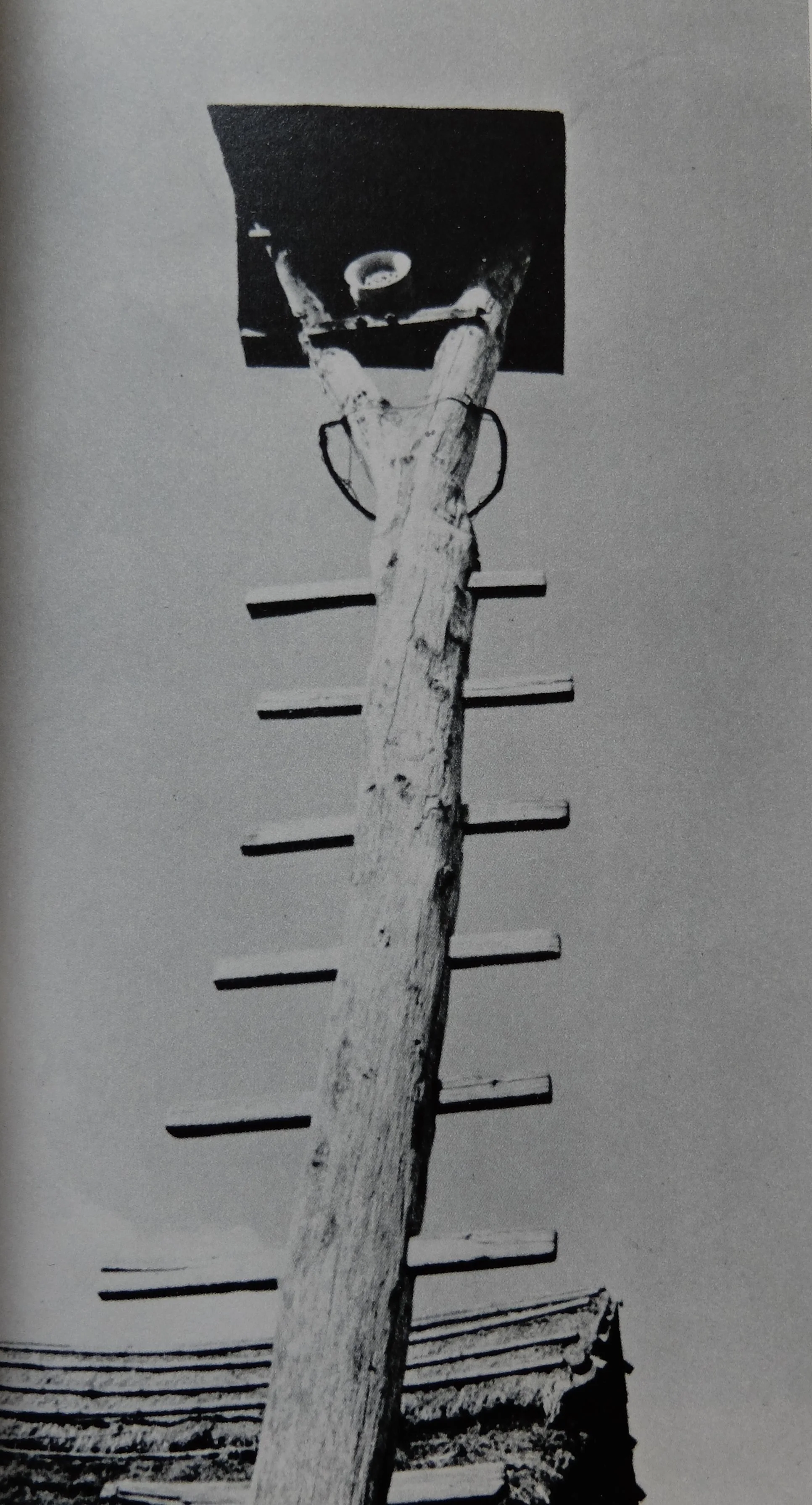

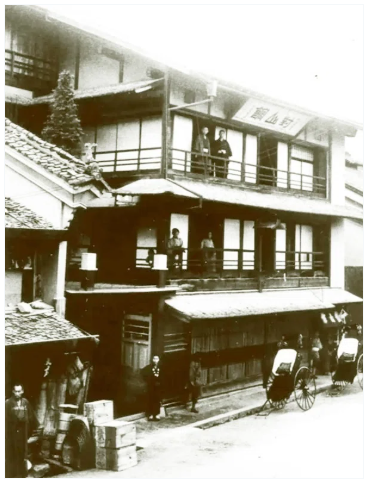

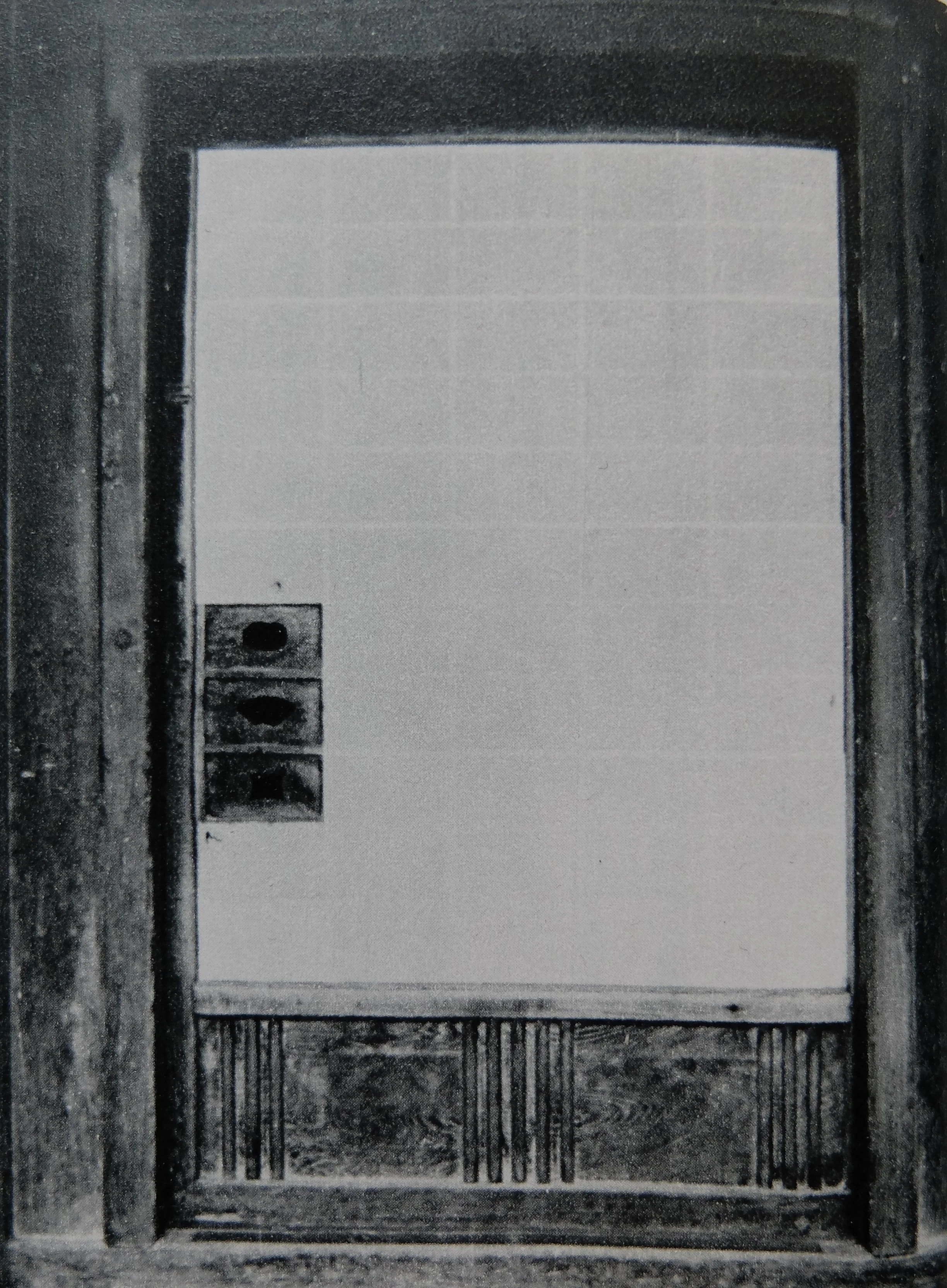

Scene showing the since-abandoned village of Hida-Kazura (飛騨加須良). The village was long without roads trafficable by cars, so preserved a purity of appearance. Gifu Prefecture.

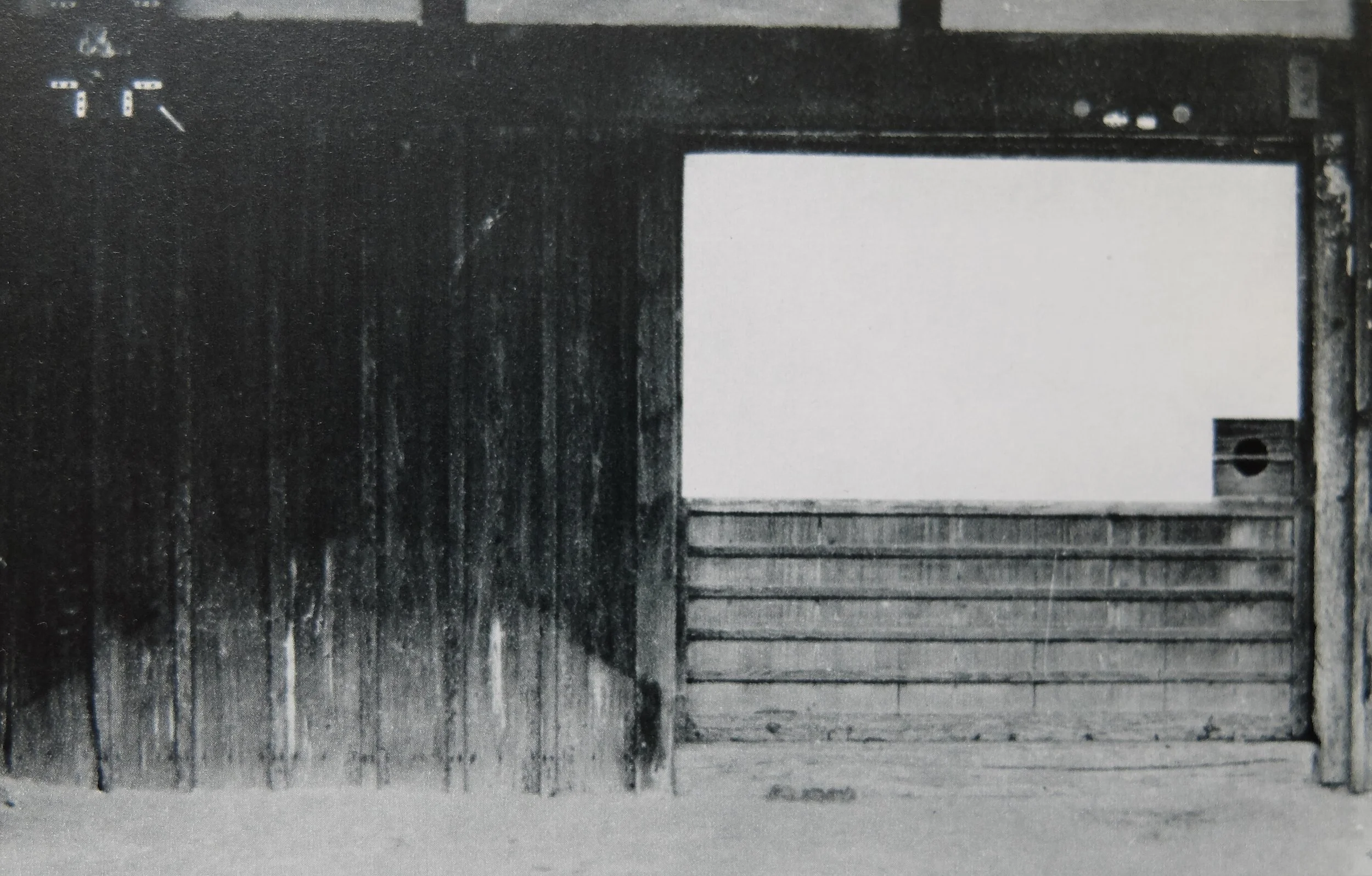

The multi-level gable-roofed gasshо̄-zukuri minka are distributed from Hida-Shо̄kawa-mura (飛騨荘川村) at the upper reaches of the Shо̄kawa river to Shirakawa-mura and the mountain villages of Ecchū Gokayama (越中五箇山). Those of Shirakawa-mura were the most famous of the style, but there are now no notable examples remaining at their original locations, following the construction of several dams and the resulting flooding. Comparatively many survive in the vicinity of Ogi-machi (荻町), part of Shirakawa-mura, but the landscape has been spoiled to a great extent: a jumbled mix of buildings, with roofs clad over with coloured sheet steel (karaa totan カラートタン) and the like. Unspoiled settlements of gasshо̄-zukuri remained in places mountain villages without bus stops, like Magari (馬狩) and Kazura (加須良) in Hida (飛騨), Katsura (桂) and Ainokura (相倉) on the Ecchū (越中) side, and in the direction of Togatani (利賀谷), but many of these places too have become deserted due to depopulation.

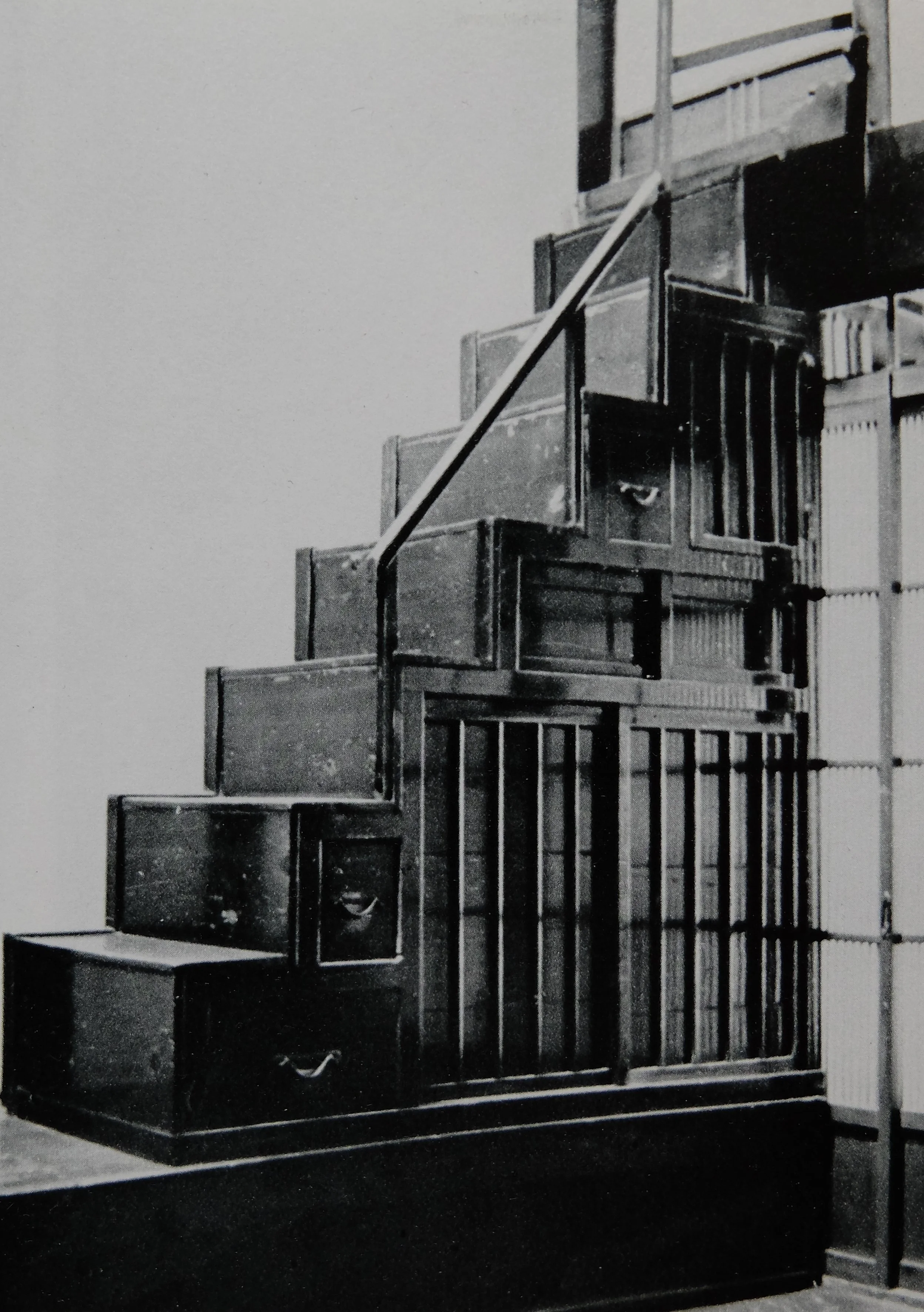

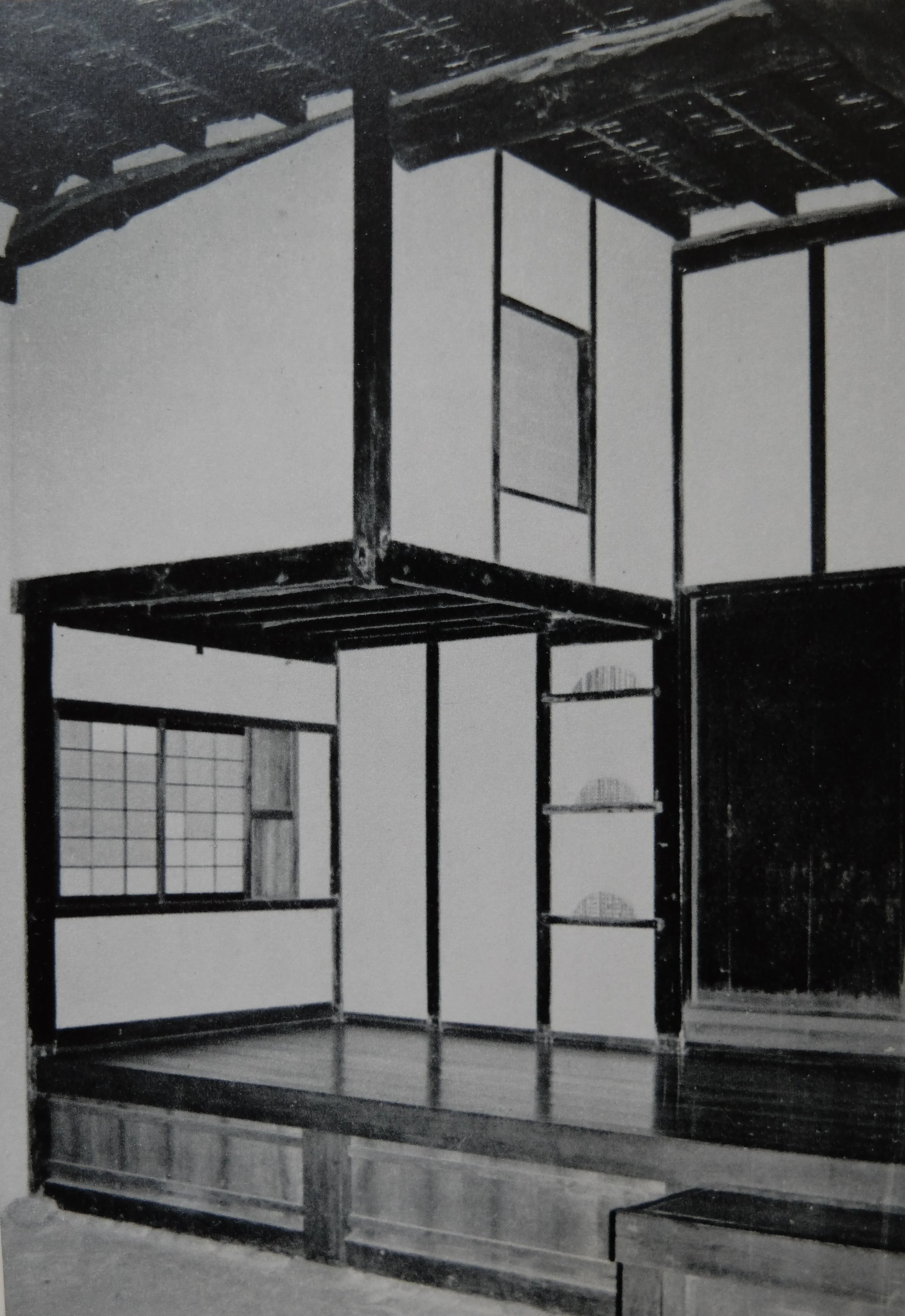

Due to the construction of a dam, there are no notable gasshо̄-zukuri minka remaining in Hida, but on the Toyama Prefecture side of the Gokayama district (Gokayama-chihо̄ 五箇山地方), several superb examples have survived, such as this one. Toyama Prefecture.

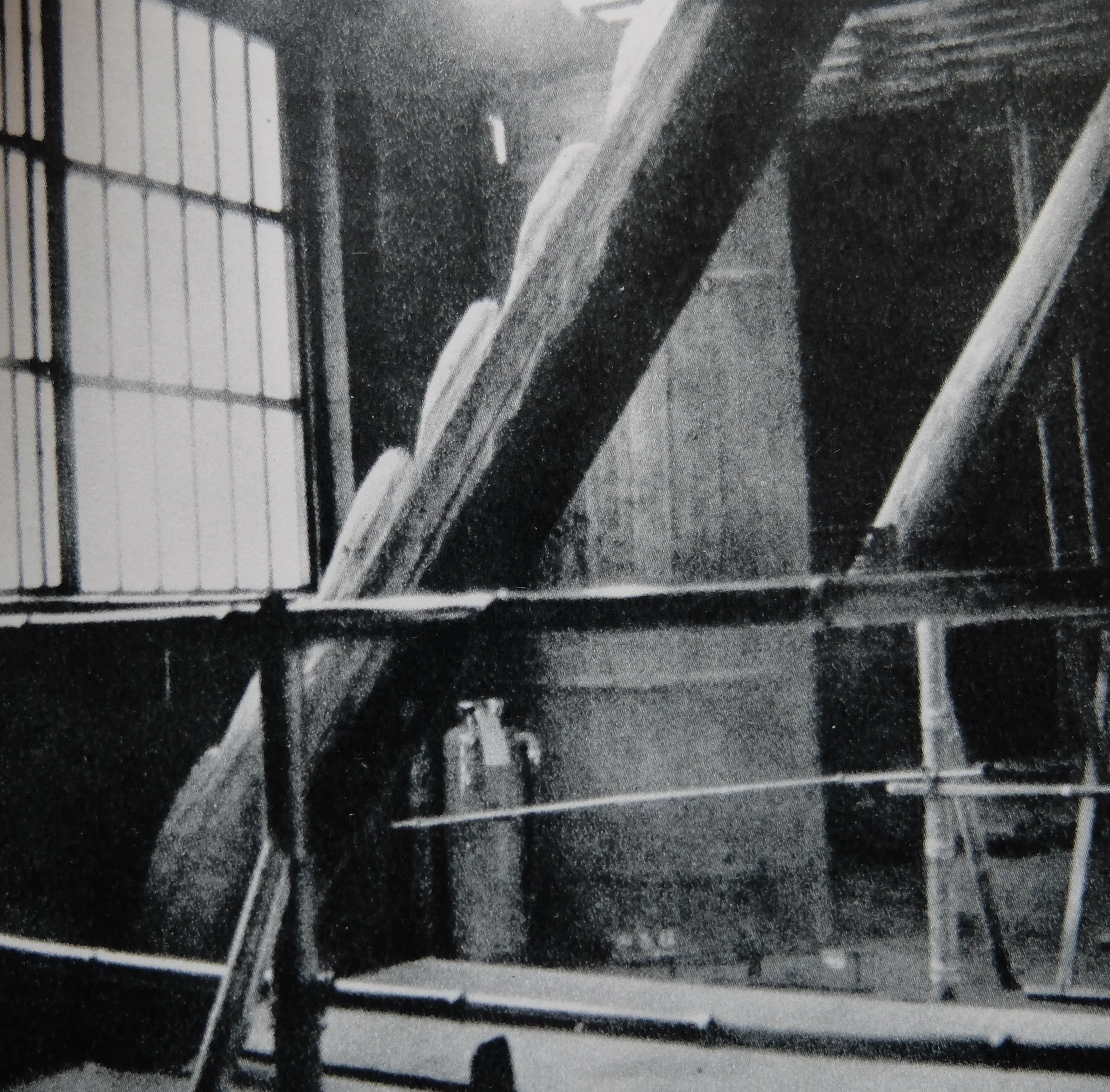

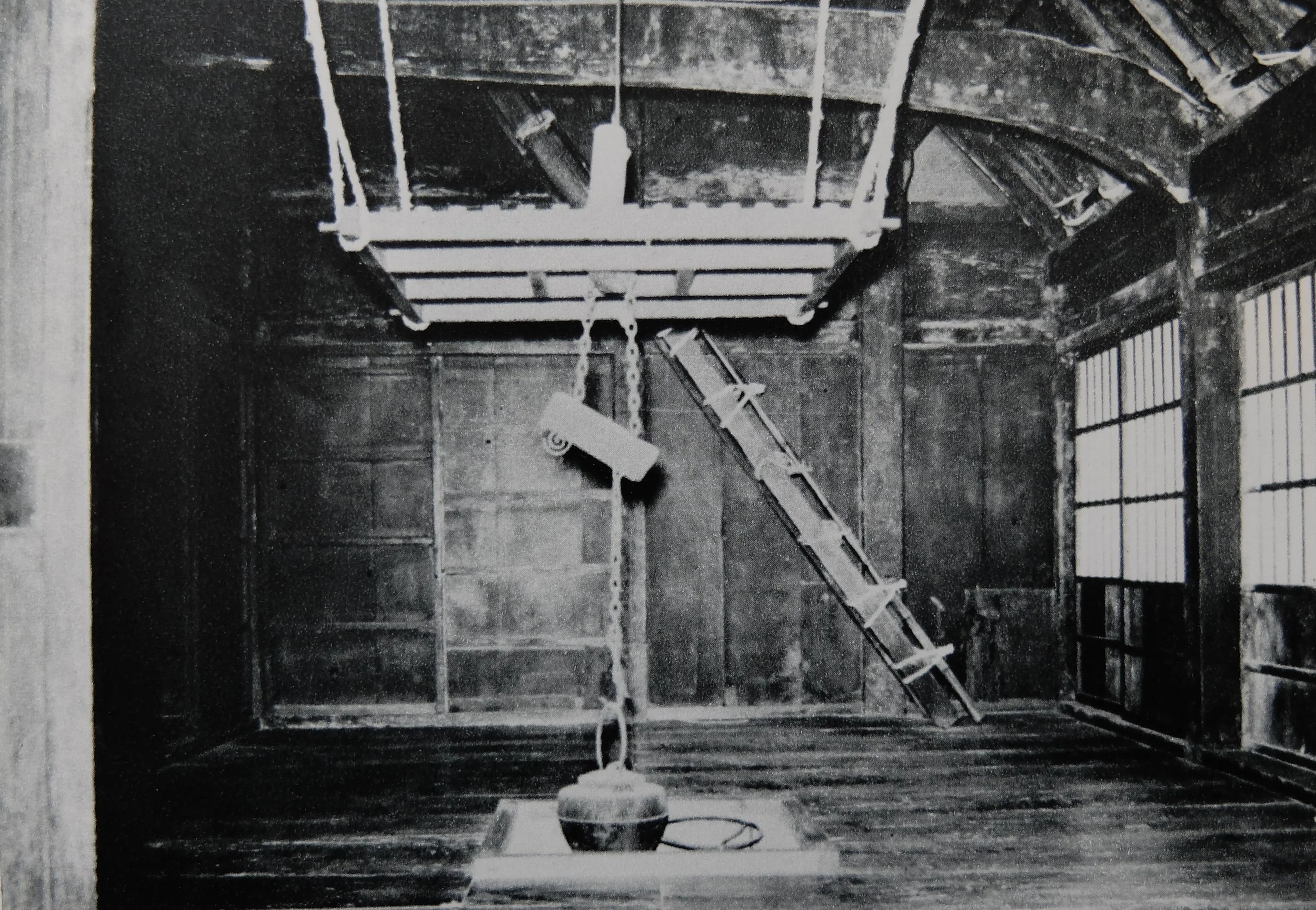

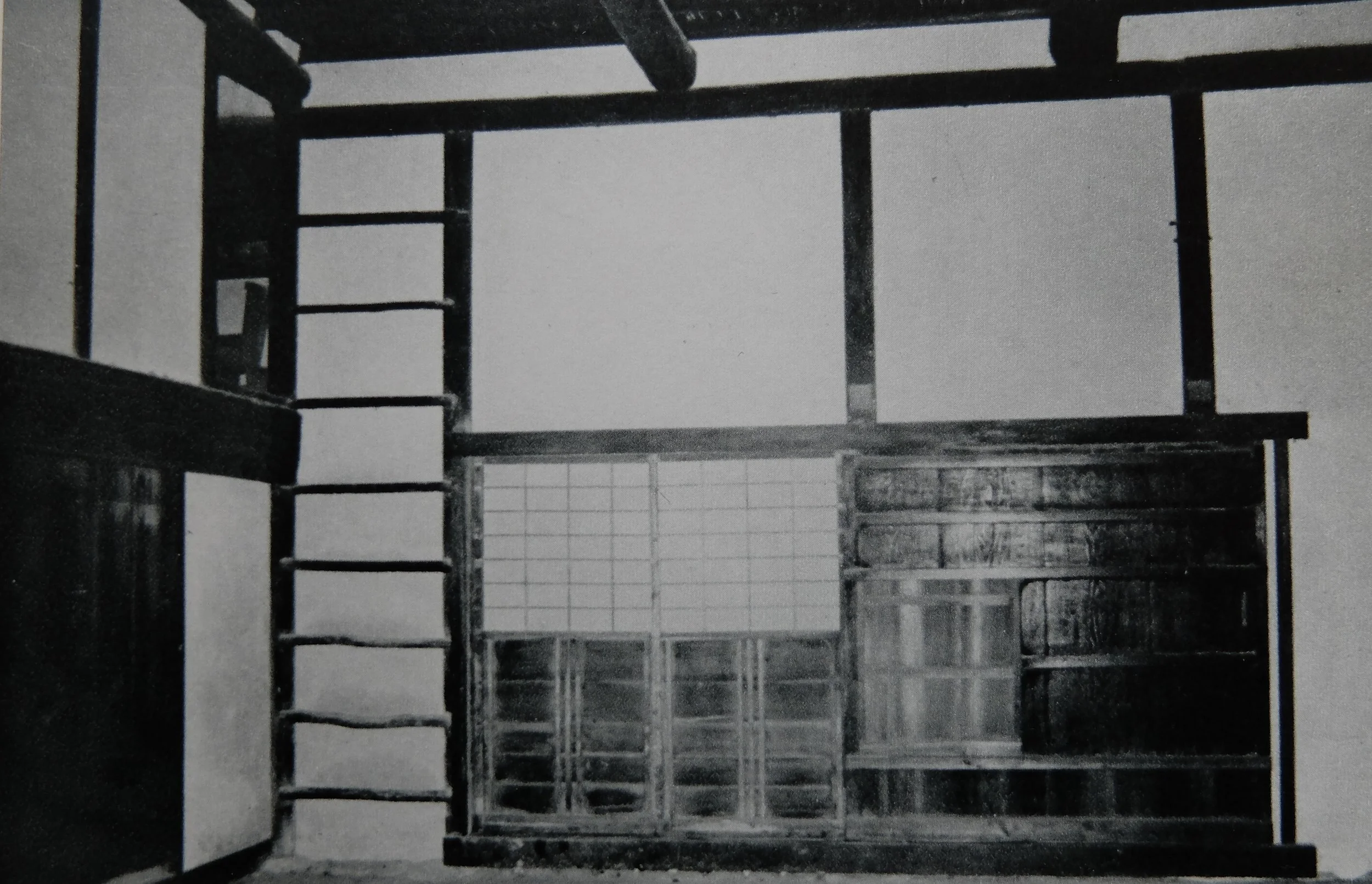

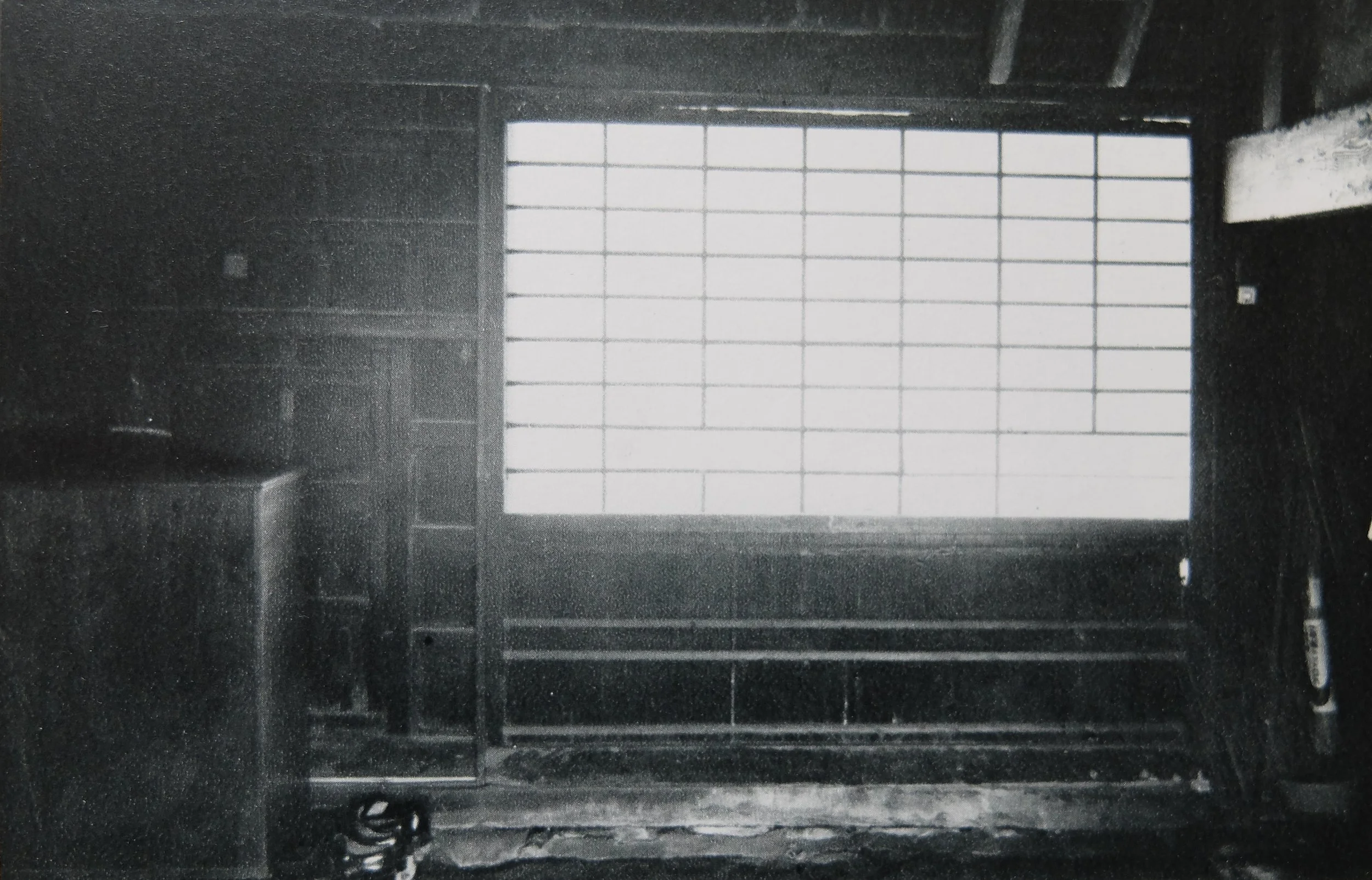

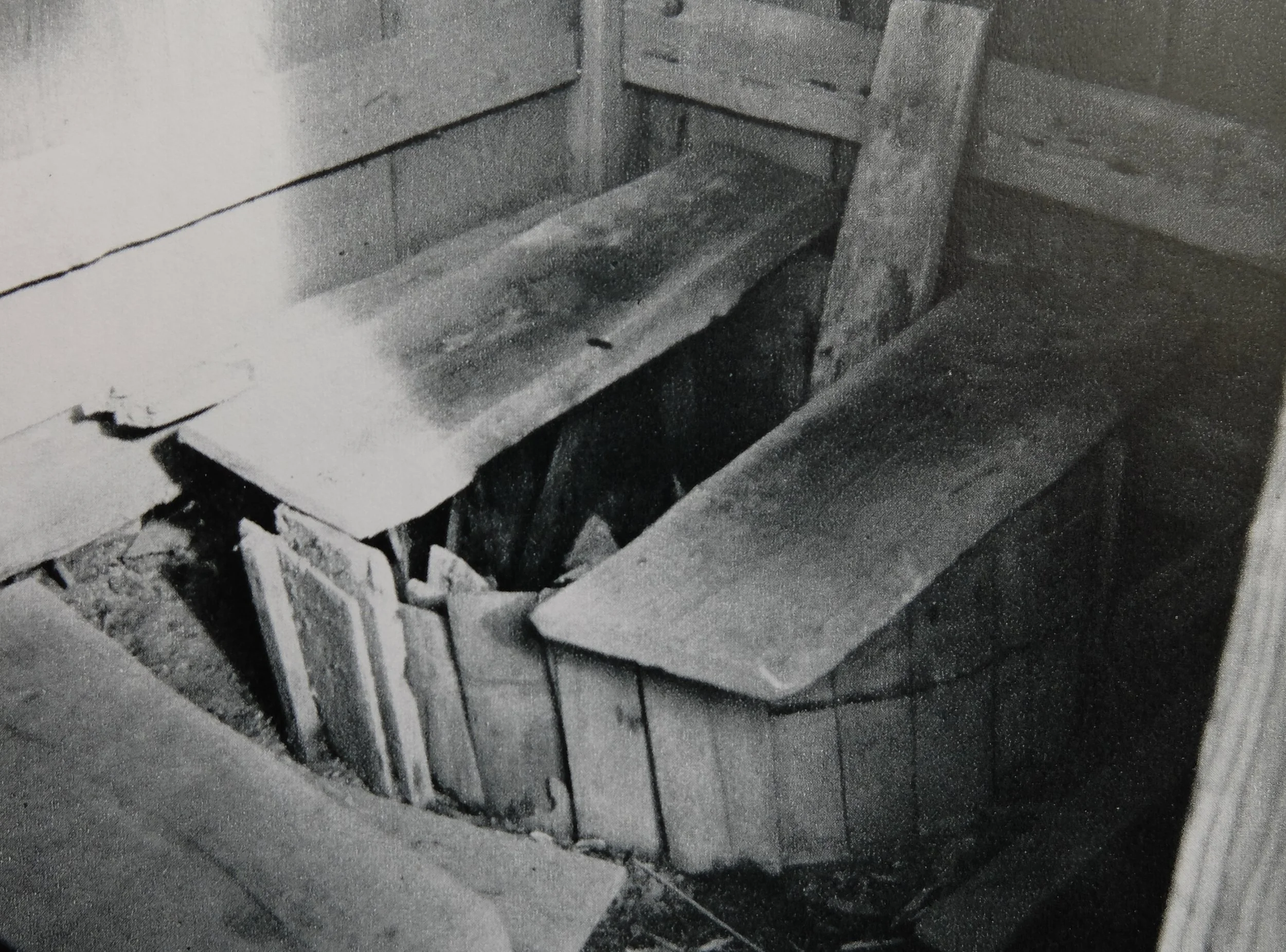

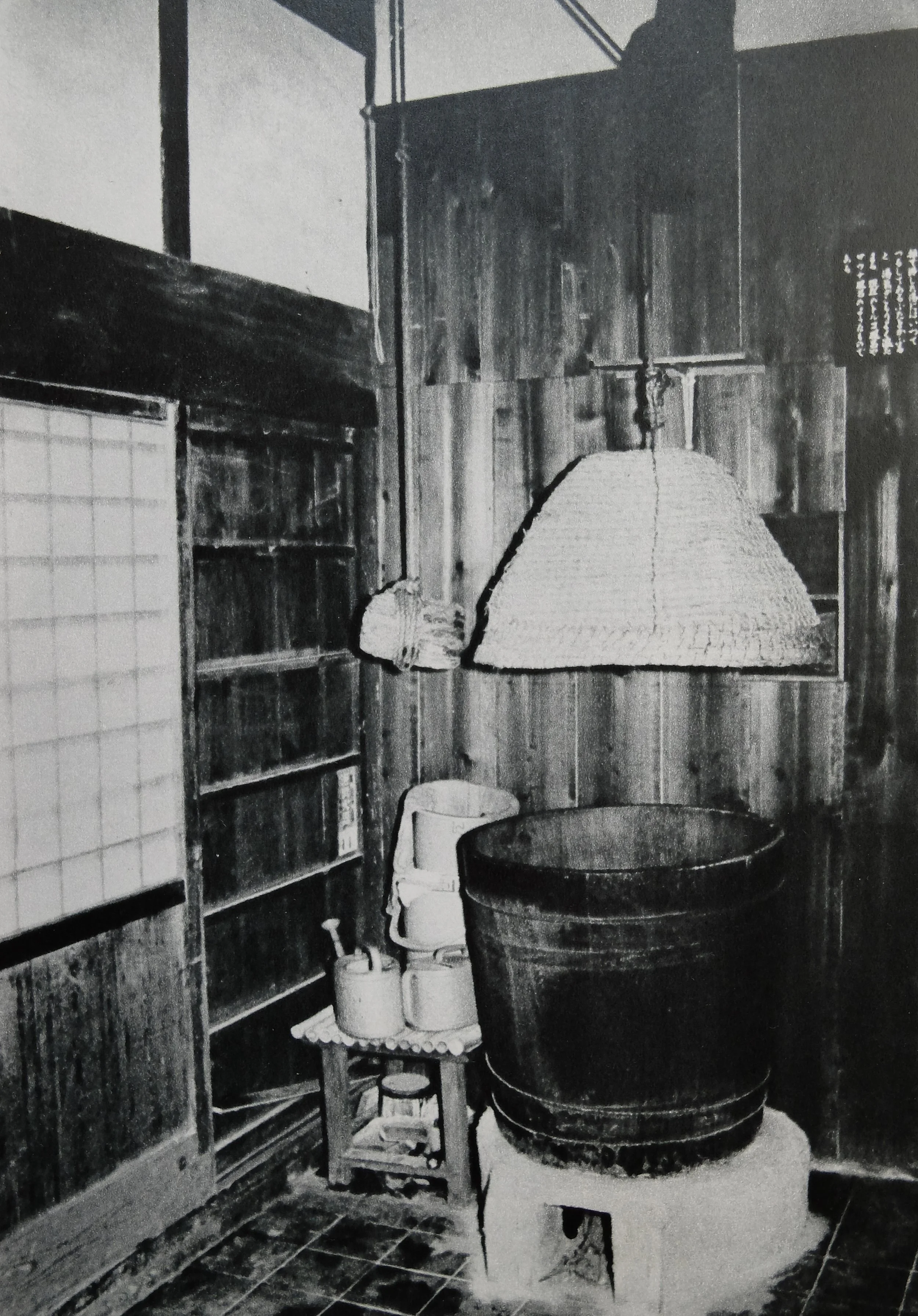

Despite the name, there is nothing particularly structurally unique about gasshо̄-zukuri; as mentioned, their roof structures are of the sasu-gumi type, the most common structural system found in thatched roof construction in Japan. Their scale is simply larger than typical, owing to the multiple levels of semi-permeable flooring, called ama (あま), incorporated into the roof spaces. Conventionally there are four levels: in addition to the ground floor (kaika 階下, ‘floor below’) habitable part (kyojū-bu 居住部), they are called the shita-ama or shimo-ama (下あま, ‘lower ama’), naka-ama (中あま ‘middle ama’), and sora-ama (そらあま ‘sky ama’). All parts of the upper levels are used for sericulture. Gasshо̄ zukuri and the ‘extended family system’ (dai-kazoku-sei大家族制) of Shirakawa-mura are well integrated; there are those who mistakenly believe that people live on each floor in the manner of an apartment building, but habitation is limited to the ground floor, though some family members may sleep in an upper chū-nikai (中二階 ‘part/half second floor’), a kind of mezzanine level.

Several factors contributed to the development of the extended family system in Shirakawa-mura. Because arable land is of limited availability in the confines of the mountains, family branching (bunke 分家, lit. ‘divide house’) could not occur; additionally, sericulture required many female hands (onna-te 女手), and as a result daughters did not leave home upon becoming brides. The eldest son (chо̄nan 長男) brought his wife into the main house to produce a successor to the family line. Other sons, too, remained living and working in the main house after marrying, but did not cohabitate with their wives, who also remained living in their own parents’ homes, where the husbands only visited them. This ‘duolocal’ arrangement is known as tsuma-doi-kon (妻問婚, ‘wife call-on marriage’).