In this post we continue with our examination of the evolution of wrapped-hiroma type (tori-maki hiroma-gata 取巻き広間型) layouts.

The plan below is an example of a two-room layout (ni-madori 二間取り) from a mountain village in Kishū (紀州), Wakayama Prefecture. There are no moveable partitions (tategu 建具) and other than the minimal exceptions of the board wall (ita-kabe 板壁) and built-in shelving (todana 戸棚) on the ‘living room’ (hiroma 広間) side of the bedroom (nema 寝間), the whole interior is left open. Interestingly, there are elements of the plan that bring to mind the layout and partitioning of the Izumo Grand Shrine (Izumo Taisha 出雲大社) in Shimane Prefecture.

The Kobayakawa family (Kobayakawa-ke 小早川家) house in Kishū (紀州), Wakayama Prefecture. A one-room dwelling (hito-ma sumai ひと間住まい) with a bedroom (nando なんど) eked out from one corner of the single room. Labelled are the utility area (niwa にわ) for agricultural work (nо̄-sagyо̄ 濃作業) and cooking (tabemono chо̄ri 食物調理); the board-floored (ita-yuka 板床) omote (おもて), whose front section fulfills the formal functions of the zashiki, for ceremonies (gyо̄ji 行事), receiving guests (sekkyaku 接客), sleeping (shūshin 就寝), and whose rear section corresponds to a daidoko or katte ‘dining room', for dining (shokuji 食事), with firepit (irori, here ro 炉) and low bench (dai 台); and the bedroom (nando なんど) for sleeping and storage (shūnо̄ 収納). The ‘verandah' (en) is used for entertaining guests (о̄tai 応対) and handwork (te-shigoto 手仕事).

Plan diagram of Izumo Grand Shrine (出雲大社)

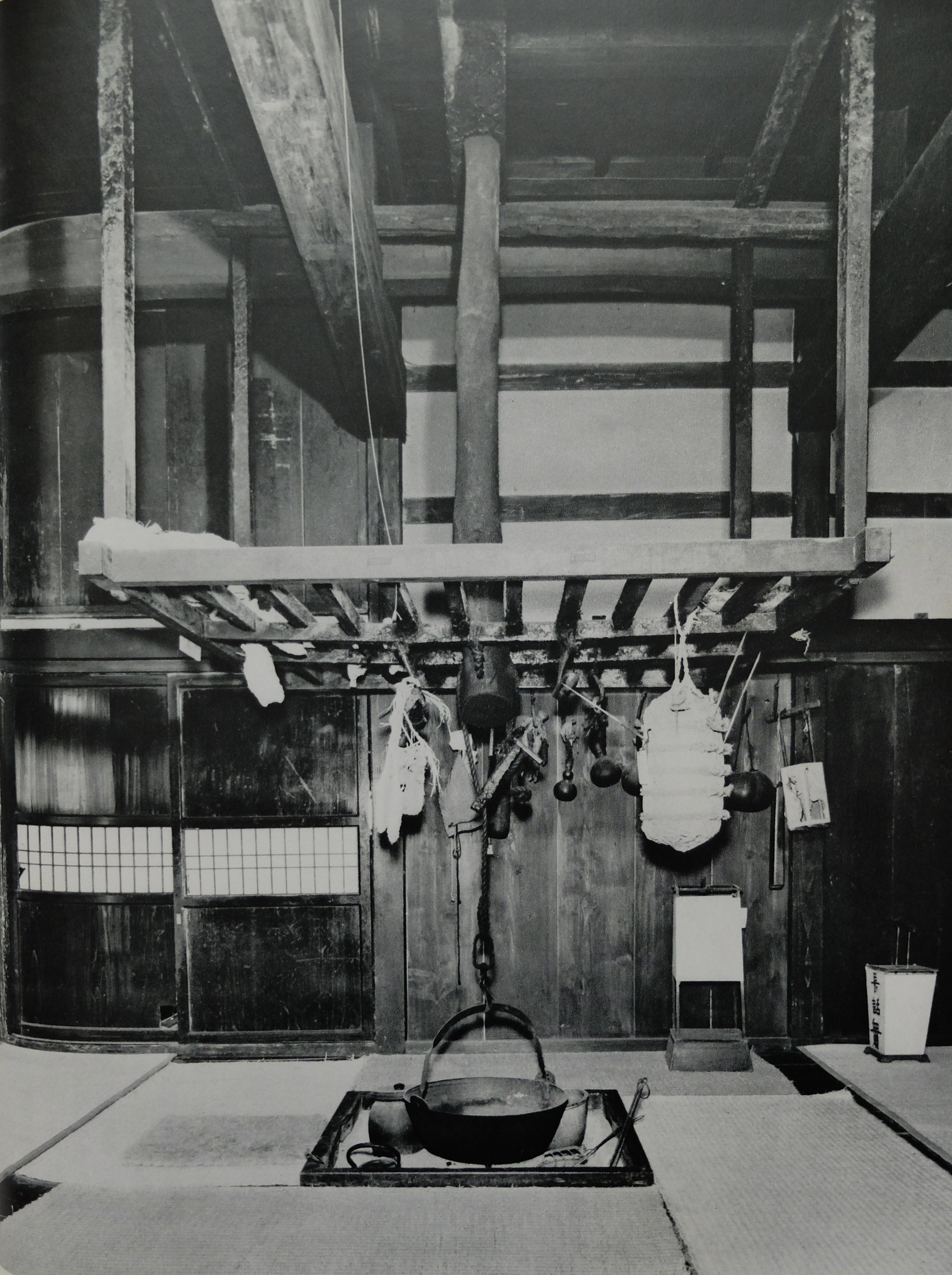

Interior view of the Kobayakawa house, looking from the omote towards the dining area with firepit (irori), and the storage area (shūnо̄) and bedroom (nando) beyond. The only interior partition is the single board-clad (hame-ita 羽目板) partition between the omote and the nando, seen here on the left; to its left is the small closet/shelves alcove.

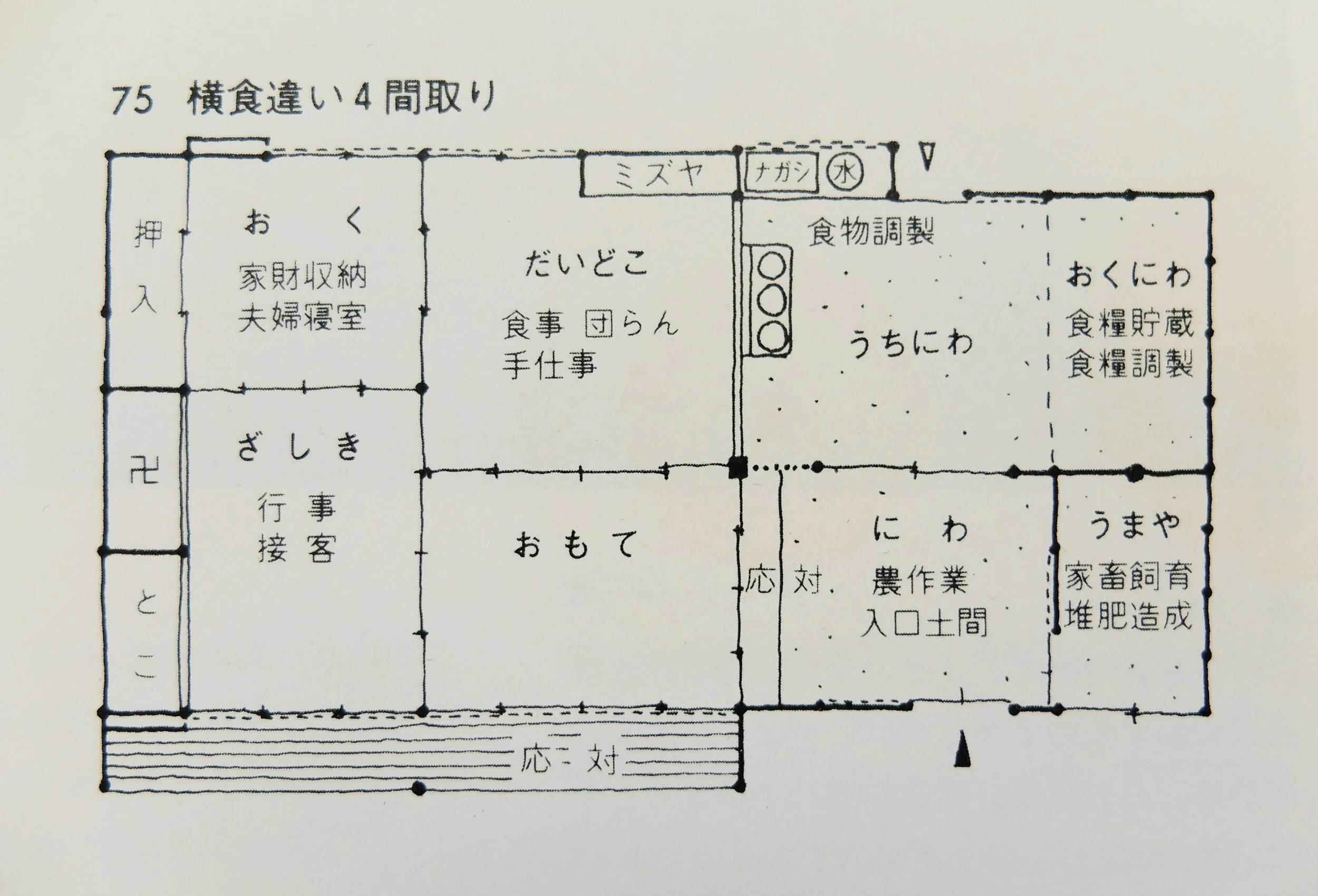

The next plan below, of the Okabe family (Okabe-ke 岡部家) house in the Okutama district (Okutama chihо̄ 奥多摩地方) of Tokyo Prefecture, is a layout often seen in the Kantо̄ region (broadly eastern Japan). If we imagine the plan without the zashiki extension (comprised of the oku おくand tobanoma とばのま), then only the husband and wife’s bedroom (the heya へや) is properly ‘walled off’. All the other room divisions are fitted with tategu, but they are normally left open; there is nothing at all in the way of fixed walls.

The Okabe house in Tokyo Prefecture. Even in such a large dwelling, if the kagi-zashiki (here the oku おく) and tobanoma とばのま) part is regarded as a later addition and the layout is considered without them, a form corresponding to (1) in the plan diagrams below is revealed, with only the bedroom (heya へや) separated off from a multi-purpose room comprised of the uchiza (うちざ) and zashiki (ざしき). Note also the massive central post. The partitions dividing off the other rooms are of various types, and still not clearly established. Labelled are: the earth-floored utility area (daidokoro だいどころ) with utility entrance (katte-guchi かって口), for farm work (nо̄-sagyо̄ 濃作業); the ito-hikiba (糸ひきば, lit. ‘thread pulling place') for secondary work (fukugyо̄ 副業), presumably including spinning; the board-floored kitchen area for cooking (suiji 炊事) with food storage (shokuryо̄ chozо̄ 食糧貯蔵), sink (nagashi ナガシ) and water (mizu 水); the dining-family room (katte かって) with fire pit (irori, marked ro 炉), for dining (shokuji 食事), family time (danran 団らん), entertaining guests (о̄tai 応対), and handwork (te-shigoto 手仕事); the zashiki (ざしき) for courting (kousai 交際)

Interior view of the О̄kubo family (О̄kubo-ke 大久保家) house in the Tama region (Tama chihо̄ 多摩地方) of Tokyo Prefecture. In everyday life the partitions are not used, and all the boundaries between rooms are left open; only the bedroom is enclosed. The layout of this house is very similar to that of the Okabe house, and the view here corresponds to that looking from the katte towards the zashiki in the Okabe house. Note again the massive central post.

Both of the above layouts are at an intermediate stage of development, on the way to transitioning into the full wrapped-hiroma type layout. They correspond to plan (1) of the plan diagrams presented in last week’s post and included again below, where a corner of the hiroma has been separated off as a bedroom.

The two layouts shown above correspond to the plan diagram (1) here, a transitional stage on the path to developing into full wrapped-hiroma layouts.