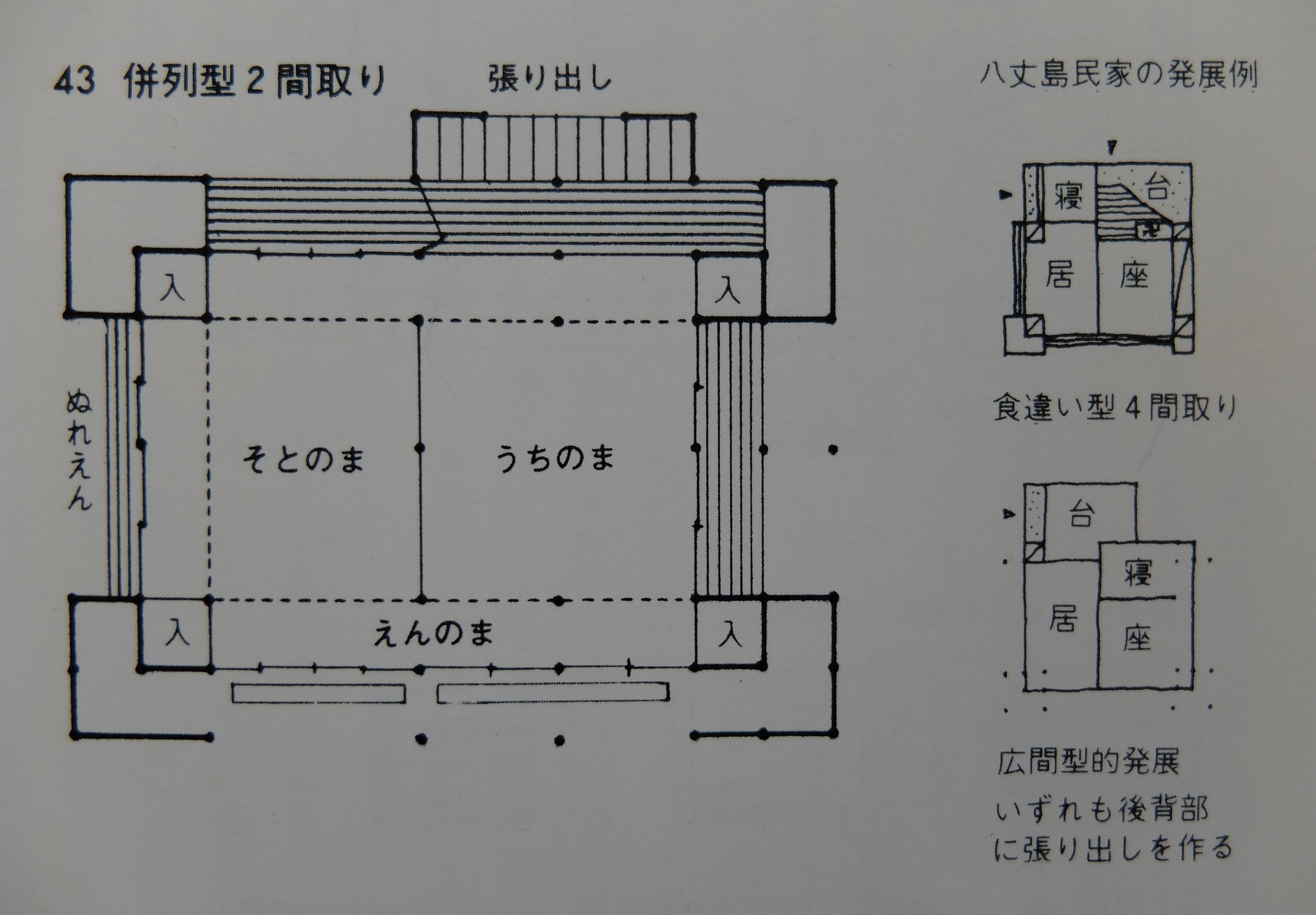

The remarkable plan shown below, with degree of symmetry rare in Japanese vernacular architecture, is of a minka on Hachijо̄ Island (Hachijо̄-jima 八丈島), about 300km south of Tо̄kyо̄. The layout is a transverse division (tate-bunwari 竪分割) longitudinal lineup (heiretsu-gata 併列型 or 並列型) two-room layout (ni-madori 二間取り), like those of the Iya district in Shikoku discussed in the previous post, but here the dining room-like space is called the soto-no-ma (そとのま, lit. ‘outside room’ or ‘outer room’), and the zashiki-like room the uchi-no-ma (そとのま, lit. ‘inside room’ or ‘inner room’). In the basic type, there is also a hari-dashi (張り出し, lit. ‘extension’) at the rear; this space is for cooking (sui-ji 炊事) and is usually called the kokku-ba (コック場, lit. ‘cook place’; kokku is possibly a loanword from the Dutch kok) in practice.

Around their perimeter the two rooms are wrapped with both enclosed corridor-like spaces called en-no-ma (えんのま or 縁の間) and unenclosed board-floored verandah-like ‘runs’ called nure-en (ぬれえん or 濡れ縁). There appears to be a fixed partition between the two rooms; to move between rooms, one would simply go around it, via the en-no-ma on either side. To strengthen the structure against typhoons, there are four posts arranged in a square in each corner of the building; in addition, each corner has an external windbreak screen called an ori-mawashi (折り回し, lit. ‘fold-around’). The space formed by the four posts in each corner is used as a closet (oshi-ire 押入, marked 入on the plan).

Development of the plan is by way of extending the thatched eave at the rear to produce a bedroom (chо̄dai ちょうだい) and transforming the kokku-ba into a partly raised-floored, partly earth-floored kitchen space. Though there are rare examples where partitions have been added and the nure-en at left and right (the gable ends) enclosed to form a three-room longitudinal lineup (san-shitsu heiretsu-gata 3室並列型) house, the more typical development path in response to an increase in the size of the family is to erect a new detached structure (hanare はなれ or 離れ, lit. ‘separate’) called a jigura (ぢぐら) alongside the main building (known as the bо̄e ぼーえ).

Plan of a minka on Hachijо̄-jima. All Hachijо̄-jima minka are, or are based on, the ‘longitudinal lineup’ (heiretsu-gata 併列型 or 並列型) two-room plan-form (ni-madori 二間取り). The plan may develop by adding or expanding the hari-dashi at the rear, as illustrated by the two smaller plans on the right: a bedroom (寝) and partly-earth floored ‘kitchen-dining’ room (台) are added to the original soto-no-ma (居) and uchi-no-ma (座). However, since there is a limit to the floor area that can be obtained by this path of development without completely altering the roof structure, often the house was expanded instead by adding separate, detached buildings such as a ‘granny flat’ (inkyo-ya 隠居家, lit. ‘retirement house’) called a jigura (ぢぐら).

External view of a minka very similar to the one shown in the plan above. Hachijо̄-jima.

An ensemble of detached buildings on Hachijо̄-jima. One of the four corner windbreak screens (ori-mawashi 折り回し) is visible on the main building (bо̄e ぼーえ), the rearmost building in the image. The structures in front of it are a raised-floor storehouses (taka-kura 高倉), fertiliser storehouses (taihi-kura 堆肥倉), or the like.

The minka plan shown below, from the island of Amami О̄shima (奄美大島), is basically the same as those from Hachijо̄-jima, with two rooms fully wrapped by a perimeter corridor called the shuen (しゅえん) and four posts in each corner. Somewhat confusingly, however, the Amami О̄shima minka is classified as a transverse lineup layout (jūretsu-gata 縦列型), not a longitudinal lineup layout (heiretsu-gata 並列型) as in the Hachijо̄-jima example, despite the fact that the rooms are ‘stacked’ or lined up along the ridgepole axis (i.e. longitudinally, at least in reference to the ridgepole) in both examples. This is presumably because the main entry to the Amami О̄shima minka is in the ‘gable wall’ (the short side) rather than in the long side of the building, making it in effect a ‘front doma’ type (mae-doma-gata 前土間型); thus ‘transverse’ in this example is considered to be along the ridgepole axis. At any rate, the distinction is somewhat moot when the doma or doma-equivalent utility space is housed in a separate building.

The omote, here called the umutei (うむてい) is the public-facing room; to the rear of this is the neisho (ねいしょ), corresponding to the family bedroom. This main building is called the uiyā (ういやー). At the rear (the gable end opposite to the entry side) the eave is extended out to form a cooking area (suiji-ba 炊事場); the opening linking this area to the shuen is called the yado-guchi (やどぐち). The path of development is as follows: the neisho in the uiyā is partitioned into two, producing another bedroom (nandon なんどん) for the husband and wife; the uiyā might then develop into a front-zashiki three-room layout (mae-zashiki-gata san-madori 前座敷型三間取り); with the growth of the family, detached buildings, such as tо̄gura (とうぐら) for living and cooking, and/or nakae (なかえ) for living and sleeping, might be successively added. This ‘separate building’ development path has its advantages and disadvantages: it allows greater privacy (though privacy was never much emphasised in traditional Japanese architecture or society), provides fire-separation, and preserves the aesthetic purity, simplicity and openness of the two-room plan; on the other hand, it requires one to go outside and ‘into the weather’ when moving between functions, which is why it is only found in the sub-tropical climates of the southernmost areas of Japan.

The larger plan on the left is of a transverse lineup type (jūretsu-gata 縦列型) two-room layout (ni-madori 二間取り) raised-floor dwelling (taka-yuka jūkyo 高床住居) on Amami О̄shima. Labelled are the living room (umutei うむてい), bedroom (neisho ねいしょ), ‘verandah’ (shuen しゅえん), rear entry (yado-guchi やどぐち), and sliding doors (to と).

The smaller plans on the right illustrate a possible path of development of this type of minka. The first plan, the basic form (kihon-gata 基本型), is a transverse lineup type (jūretsu-gata 縦列型) two-room layout (ni-madori 2間取り). The single building, the uiyā (ういやー), contains a living room (za 座) and bedroom (ne 寝), with a lean-to (geya 下屋) at the rear for cooking (sui 炊). In the second plan, the bedroom is divided to obtain a second bedroom or storeroom (nо̄ 納), resulting in a front-zashiki type three-room layout (mae-zashiki-gata san-madori 前座敷型3間取り), and a separate building (hanare 離れ) called tо̄gura (とうぐら) is added; the tо̄gura contains a living room (i 居) and kitchen (sui 炊). The two buildings are connected by a short corridor. In the third plan, the second building becomes the nakae (なかえ) with living room (i 居) and bedroom (ne 寝), and the title tо̄gura (とうぐら) is transferred to a third building, an earth-floored cookhouse (sui 炊).

External view of a minka on Amami О̄shima of the same layout as that shown in the plan above. The perimeter of this minka is different to the open ‘verandah’ (engawa 縁側) typically found on mainland minka: here it is enclosed with board walls (ita-kabe 板壁). Unusually for Amami О̄shima, the building features a shingled (koba-buki こば葺き) roof. This has the advantage of allowing a significantly shallower roof pitch than is possible with thatch (which would leak), thus reducing wind loads on the roof in a typhoon-prone region.

Exterior view showing the ‘separate buildings’ path of development of Amami О̄shima minka. In this case the total house consists of two buildings (ni-tou 2棟, lit. ‘two ridges’). In the foreground on the right is the main building (shuya 主家) called the uiyaa (ういやー); on the left behind it is the ‘cookhouse’ (suijitо̄ 炊事棟) called the tо̄gura (とうぐら). The two buildings are connected by a short corridor (watari-en 渡縁).