After devoting the last eight posts or so to three-room layout (san-madori 三間取り) minka, today we move on to four-room layouts (yon-madori 四間取り), though four-room layouts have already made many appearances in these posts, in considering the paths of development of one-room, two-room and three-room minka in response to increasing familial requirements or general economic advancement.

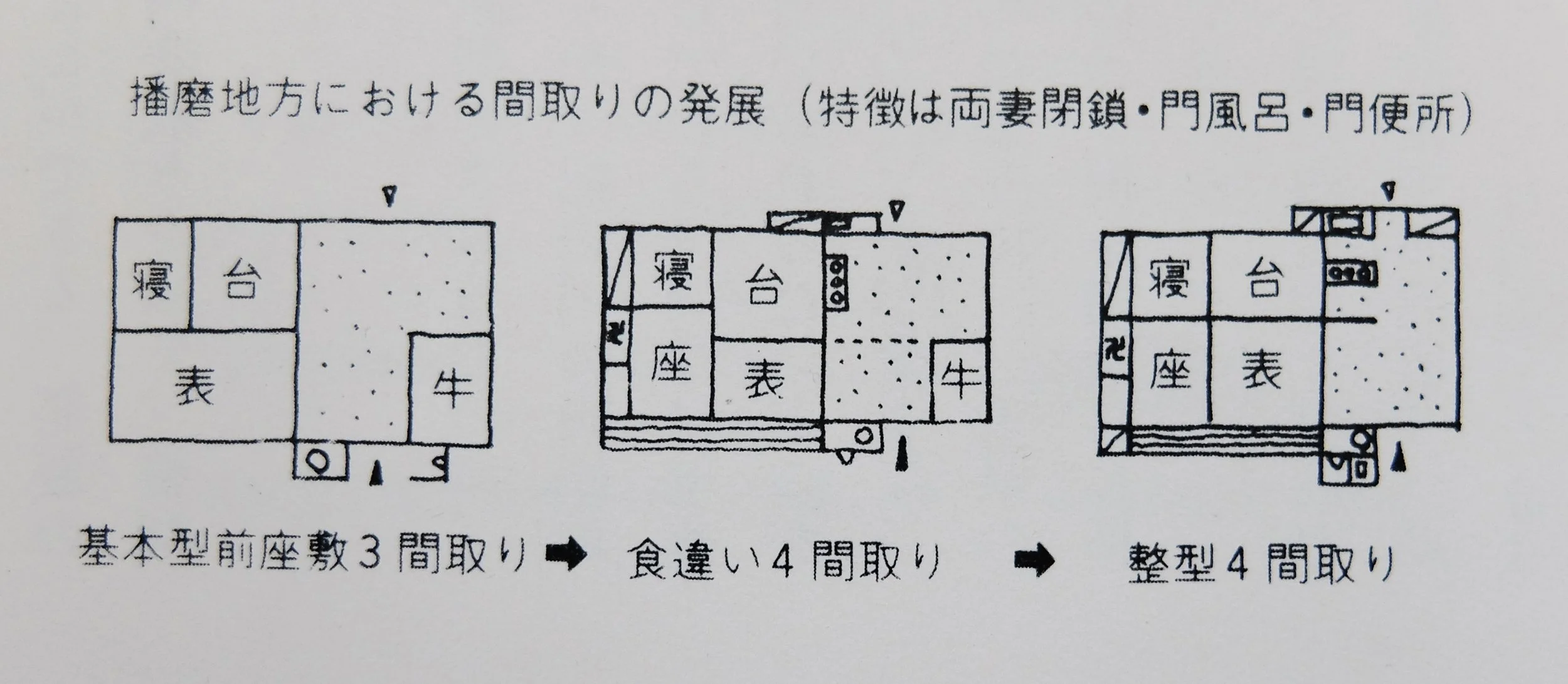

As the name suggests, the ‘floored’ or ‘habitable’ part of the four-room layout minka consists of four rooms, not including the earth-floored utility space called the doma (土間). In general, four-room layouts are sub-categorised as either regular (seikei 整形) or ‘irregular’ or staggered (kui-chigai 食違い).

In the regular form, the corners of the four rooms intersect at a single, central point, with the two perpendicular partition lines in a cruciform (jūji-kei 十字形) arrangement; this layout is also known as ta-no-ji-gata madori (田の字型間取り, lit. ‘rice paddy character type layout’), for its resemblance in plan to the character for rice fields (ta,田). In the irregular or staggered form, one of the partitions between two rooms is offset from the intersection.

Hypothetical plans illustrating the two sub-categories of four-room layout (yon-madori 四間取り). On the left is a ‘staggered' layout (kui-chigai gata 食違い型); in this case it is a ‘hiroma type’ (hiroma-gata 広間型) layout, with the ‘stagger’ in the partition line being perpendicular to the room-doma boundary, further classifying it as a ‘perpendicular staggered type’ (yoko kui-chigai gata). The plan on the right is a regular (seikei 整形) four-room layout (yon-madori 四間取り). Earth-floored utility areas (doma 土間) are not shown, but should be imagined on the right of each plan; i.e. in the first plan the ‘living room’ (hiroma ひろま) and ‘kitchen/dining room’ (katte かって) border the doma, and in the second plan the katte and ‘living room’ (dei でい) border the doma.

Given that minka typically lack internal corridors, one advantage of the staggered layout over the regular layout, apparent from looking at these two plans, is that the staggered layout gives two of the rooms direct access to all three of the other rooms. In the example above, one can go between ‘living room’ (hiroma ひろま) and bedroom (heya へや) without entering either the ‘kitchen/dining room’ (katte かって) or the ‘formal room’ (zashiki ざしき), whereas in the regular layout, one cannot go from the ‘living room’ (dei でい) to the heya except via either the katte or the zashiki. This ‘universal access’ functionality can be given to any room according to the placement of the ‘stagger’, but for obvious reasons it usually goes to the room that corresponds most closely to the western idea of the ‘living room’, i.e. the room that acts as the functional hub of the house.

The four-room layout can be thought of in a sense as a complete, fundamental form, or at least a developmental culmination. In the Kinki region, where minka development was at its most advanced, the four-room layout became common beginning from around the early Edo period (i.e. the early 17th century). Development beyond this point, at least among the farmhouses of high-status families, was into regular six-room layouts (seikei roku-madori 整形六間取り), with such sub-classifications as sa-ji-gata (サ字型, lit. ‘sa character type’) and ki-ji-gata (キ字型, lit. ‘ki character type’). Each of these forms might be considered an elaborative result of uniquely complex developmental ends, and it is difficult to neatly organise them into coherent types or categories.

As mentioned, there was a nation-wide tendency for all types of layout to find developmental fulfilment in the four-room layout, and this layout has become the representative form of Japanese vernacular dwellings in the ‘modern’ era. In previous eras, the hiroma-gata three-room layout had made up the majority of minka layouts, but with the four-room layout there is the division of the hiroma into two rooms. It is thought that one of the factors that motivated the development of an independent ‘dining room’ and the breaking up of the irori-centred ‘dining - family time - hosting guests’ triad was the desire to improve the liveability of the dwelling in general, and in particular to eliminate the various inconveniences and impracticalities involved with receiving guests in the place of eating. There was also sometimes the economic necessity of taking up sericulture (yо̄san 養蚕), and the consequent need to be able to close up a room or rooms to retain the warmth required for raising (yо̄-iku 養育) young silkworms (chisan 稚蚕).

The facade-side room resulting from the division of the hiroma is called variously the dei (でい), de (で), denoma (でのま), kuchinoma (くちのま), shimonoma (しものま), omote (おもて), ima (いま), genkan zashiki (玄関座敷), etc.; the names all indicate either the use or position of the room, which functions as the space for reception (о̄tai 応対) and living activities, an entry for honoured guests, and a ‘breakout’ or ‘spillover’ extension of the zashiki when conducting religious ceremonies (gyо̄ji 行事).