This post is the last on Japanese stoves (kamado 釜土), and will simply present more examples, if only to give a sense of the great variety of kamado that once existed in minka.

The picture below shows a small ‘two-burner’ kamado in a house north of Lake Biwa. It is located in the dwelling’s earth-floored ‘habitable doma’, known in this area as the niuji (にうじ). Likewise, in this region the kamado is called the fudo, and the large ceremonial kama, the о̄-kama (大釜 ‘big kama’), is called the о̄-fudo. The niuji is swept clean until it appears polished, and wearing footwear in it is not allowed. A mat (goza 茣蓙) is laid on the earth floor in the framed area in front of the kamado.

The fudo in an earth-sitting dwelling (doza-sumai 土座住まい). The doma is kept impeccably clean, and shoes are not allowed to be worn in it. The stove is tended from the reed mat (goza 茣蓙) laid in front of it. Hirai family (Hirai-ke 平井家) residence, Shiga Prefecture.

Below is a kamado from a minka at the foot of Mt. Akagi (Akagi-yama 赤城山) in Gunma Prefecture; here the kamado is called hettsui. This example is built into one corner a deep, stone-lined irori; the wife tends both the irori and the hettsui from the ki-jiri (木尻) position between the irori and the doma, from the ki-jiri-dai (木尻台, ‘wood tail platform), which is a step down in level from the main floor.

A kamado built into a corner of the irori, expressing a division of function: the kamado is used for ‘boiling’ (ni-taki 煮炊き) cooking. Akuzawa family (Akuzawa-ke 阿久沢家) house, Gunma Prefecture.

The image below, from Tottori Prefecture, shows an example of a kamado built on the sill (agari-kamachi 上がり 框) side of the kaka-za (かか座), the wife’s seating position, from which the irori and kamado are used in combination for cooking.

A kamado built next to the wife’s seat (kaka-za 嚊座) at the irori, at the edge of the doma. The irori is used only for heating, and boiling water. Tottori Prefecture.

Below is an example of an old, primitive style of kamado: the pot or kettle rests on three stones placed in the irori, which is surrounded by a timber frame. This example is from Amami-О̄shima (奄美大島).

A primitive kamado suggestive of the kamado’s origins, consisting of three stones plastered with clay. Kagoshima Prefecture.

The picture below is an example of how, in regions with cold climates, there is a tendency over time for the kudo to sidle up to the raised, board-floored ‘living room’ or multi-purpose room; a duckboard or slat panel (sunoko 簀の子) is placed in front of the kudo, or a low board floor built there, from which to tend the stove.

Here the kamado has drawn up to the edge of the multi-purpose room. The sink area behind it has already acquired a board floor (and modern kitchen unit); next in the modernisation of the doma, a timber slat floor panel (sunoko 簀の子) would be laid in front of the kamado, then this area too would eventually be floored. Kyо̄to City.

In even colder climates, the kudo is moved right up into the board-floored ‘kitchen’ or daidoko, which also contains an irori, as shown in the image below; the irori and kudo are united within a single perimeter frame. The mountainous region of northern Kyо̄to Prefecture is once such area.

Here the kudo has migrated to the centre of the gathering room for eating and family time (danran 団らん). The irori and the kamado are enclosed within the same frame. Kyо̄to.

Kudo in Kinki region prefectures such as Kyо̄to and Nara are, as in the picture below, often built in a semi-circular magatama plan-form, and carefully finished in fine plaster. After being smoothed with a trowel (kote 鏝), the plaster is polished with camellia (tsubaki 椿, Camellia japonica) leaves.

A seven-burner kudo in the Rakuhoku (洛北) district in north Kyо̄to City. The curved plan-form allows a single person to tend each fire and pot from a central position.

The kamado shown below is in the doji (doma) of the Tsurutomi villa (Tsurutomi-yashiki 鶴富屋敷), built in the early 19th century, in Shiiba village (Shiiba-son 椎葉村), Miyazaki Prefecture. The stove consists of two units: a two-burner stone о̄-kama, and a smaller two-burner kamado for everyday use. The board-floored area behind the stove is called kama-no-ushiro (釜の後ろ, ‘stove’s behind’), kama-sedo (釜背戸, ‘stove back door’), etc., and is used for food preparation and serving.

A two-part, four-burner kamado for both formal and everyday uses. Miyazaki Prefecture.

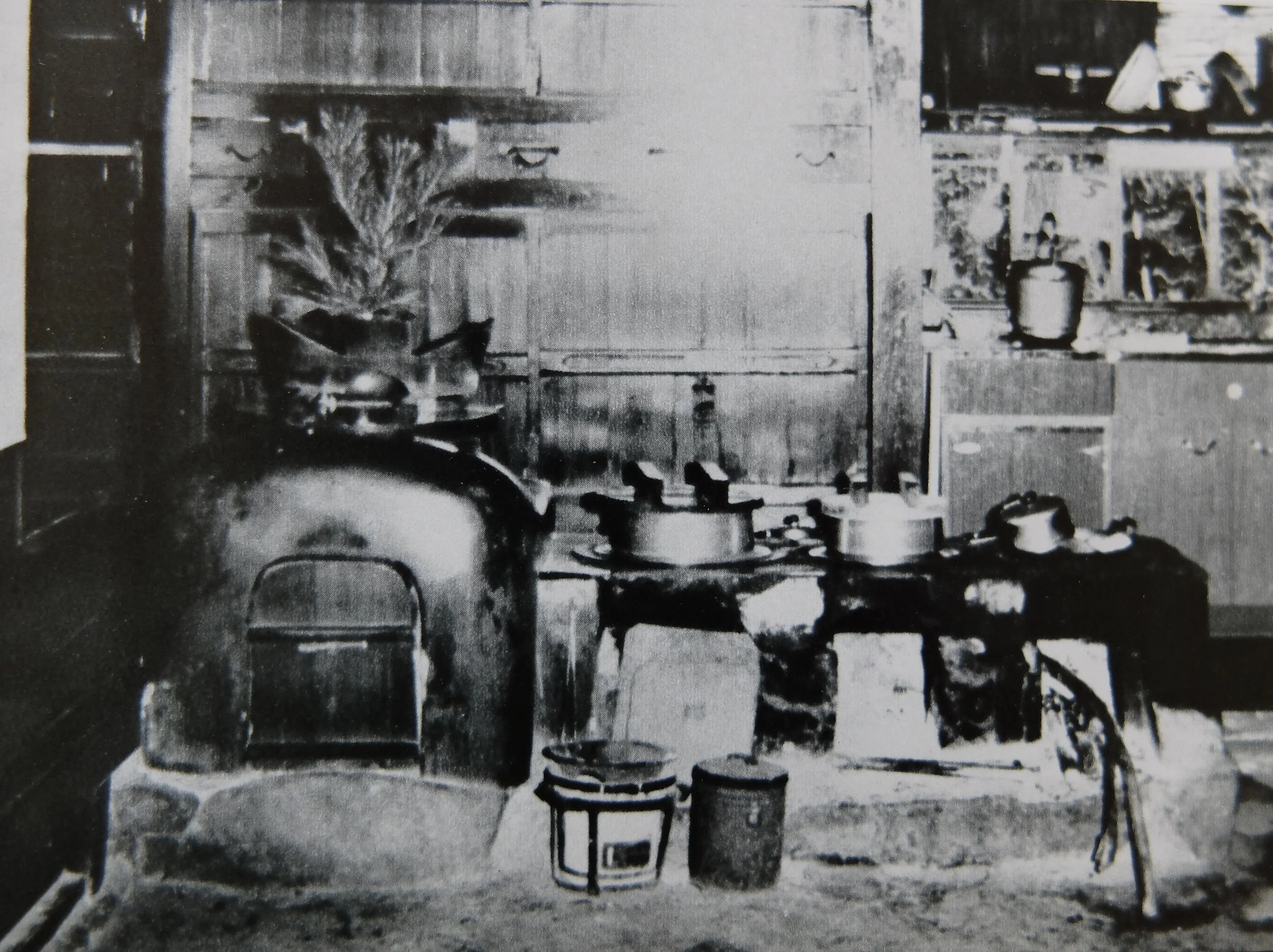

Below is a kudo installed in the tо̄ri-niwa (通り庭) of a townhouse (machiya 町家) in Kyо̄to City. The tо̄ri-niwa is the long ‘strip’ doma that runs the full length of the narrow machiya, from the street to the rear. From right to left in the picture is the white-plastered о̄-kama-sama, the to-gama (斗釜, ‘to stove’; one to 斗 is 18.039 litres), and the roku-dai (六台, lit. ‘six platform’, presumably a six-burner unit), only partly visible.

A kudo in the tо̄ri-niwa of a Kyо̄to townhouse (kyo-machiya 京町家). The о̄-kama-sama is decorated with a pine branch.

Finally, the picture below shows another о̄-kama-sama (大釜様, ‘honorable big stove’; sama is an honorific, more formal and respectful than san) in Kyо̄to adorned with pine and sakaki branches, enshrining the stove deity. It is not used day-to-day, but only on formal occasions.

An о̄-kama-sama adorned with pine and sakaki branches. Inoue family (Inoue-ke 井上家) residence, Kyо̄to.