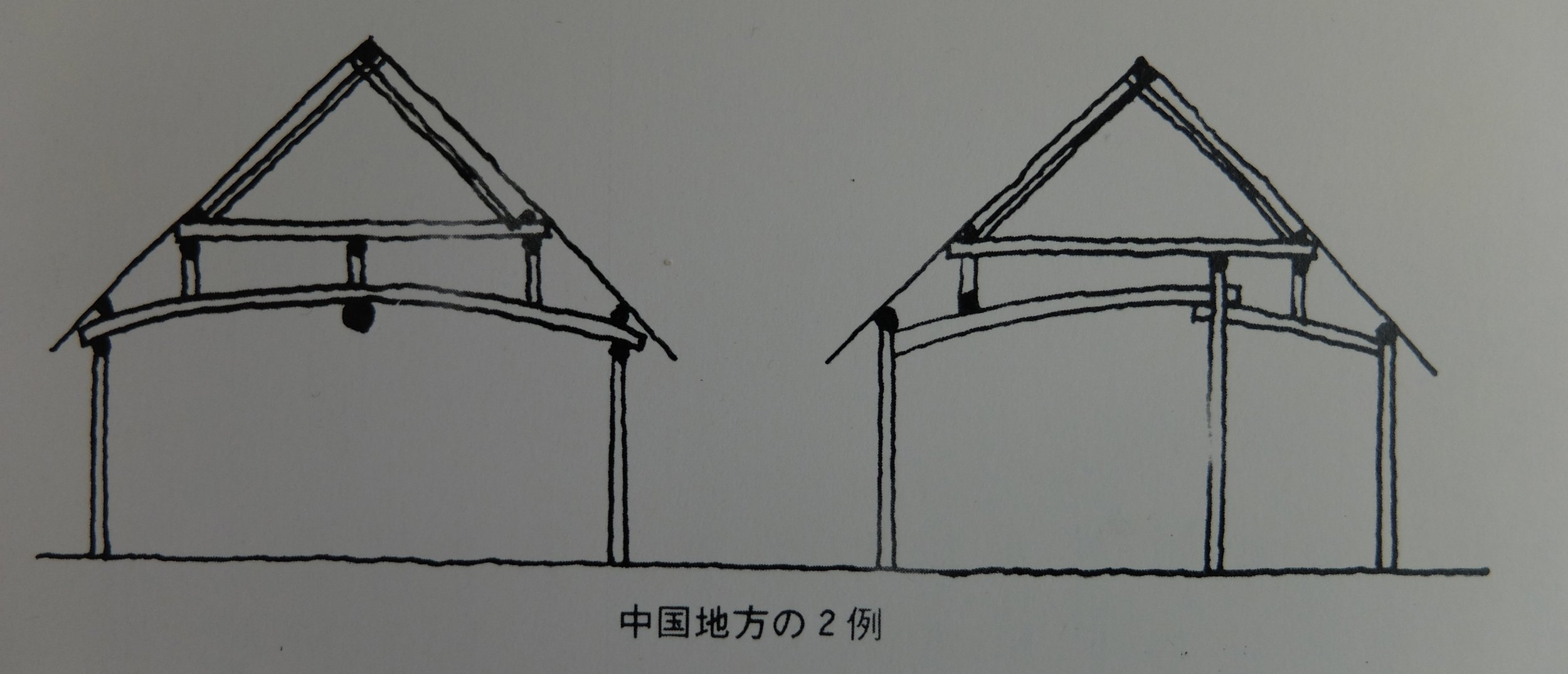

In cold areas where the snow load on roofs is great, and in large minka where the principal rafters (sasu 叉首) are especially long, roof posts (tsuka 束) are employed at intermediate positions to support the sasu and prevent them from sagging or bending. These posts, in conjunction with the transverse ties or beams that sit on top of them, form a shape that resembles the Shinto torii (鳥居) gate, and so this reinforced sasu-gumi construction is known as torii-gumi (鳥居組). This is something of a hybrid style of construction, somewhere between true sasu-gumi, where the sasu are unsupported along their length, and true wagoya-gumi, where there are no sasu. The transverse elements also serve to prevent the sasu from thrusting outwards and spreading the walls that they terminate on.

A torii gate.

Torii-gumi construction.

Thanks to the trussed form created by the paired sasu and the transverse member that forms the base or bottom chord of the triangle, sasu-gumi structures are very strong in the transverse direction, but they are extremely prone to racking or tipping over in the longitudinal direction.

Various methods have been devised to compensate for this longitudinal weakness. The idea for sasu is thought to have originated in haza (稲架), the simple pole structures erected in paddy fields to dry harvested rice. Stability in these structures is achieved by adding a third leg to the ‘sasu’ pairs at each end to form tripods which brace the structure against longitudinal forces.

In minka roof framing, the equivalent ‘third leg’ members at the ‘gable’ ends (妻側 tsuma-gawa) or short sides of hipped roofs are called oi-sasu (追叉首, lit. ‘following principal rafter’) or mukau-sasu (向かう叉首, lit. ‘facing principal rafter’), in contrast to the ‘regular’ paired sasu in the long sides of the roof, which are called hira-sasu (平叉首, lit. ‘flat principal rafter’). The oi-sasu is tenoned into the underside of the ridgepole (munagi 棟木) just to the outside of the point where the end pair of hira-sasu cross.

Photograph showing how the oi-sasu (追い叉首) is tenoned up into the munagi (棟木) just to the outside of the paired hira-sasu (平叉首, here called sashiki さしき).